Author: Sven Wunder

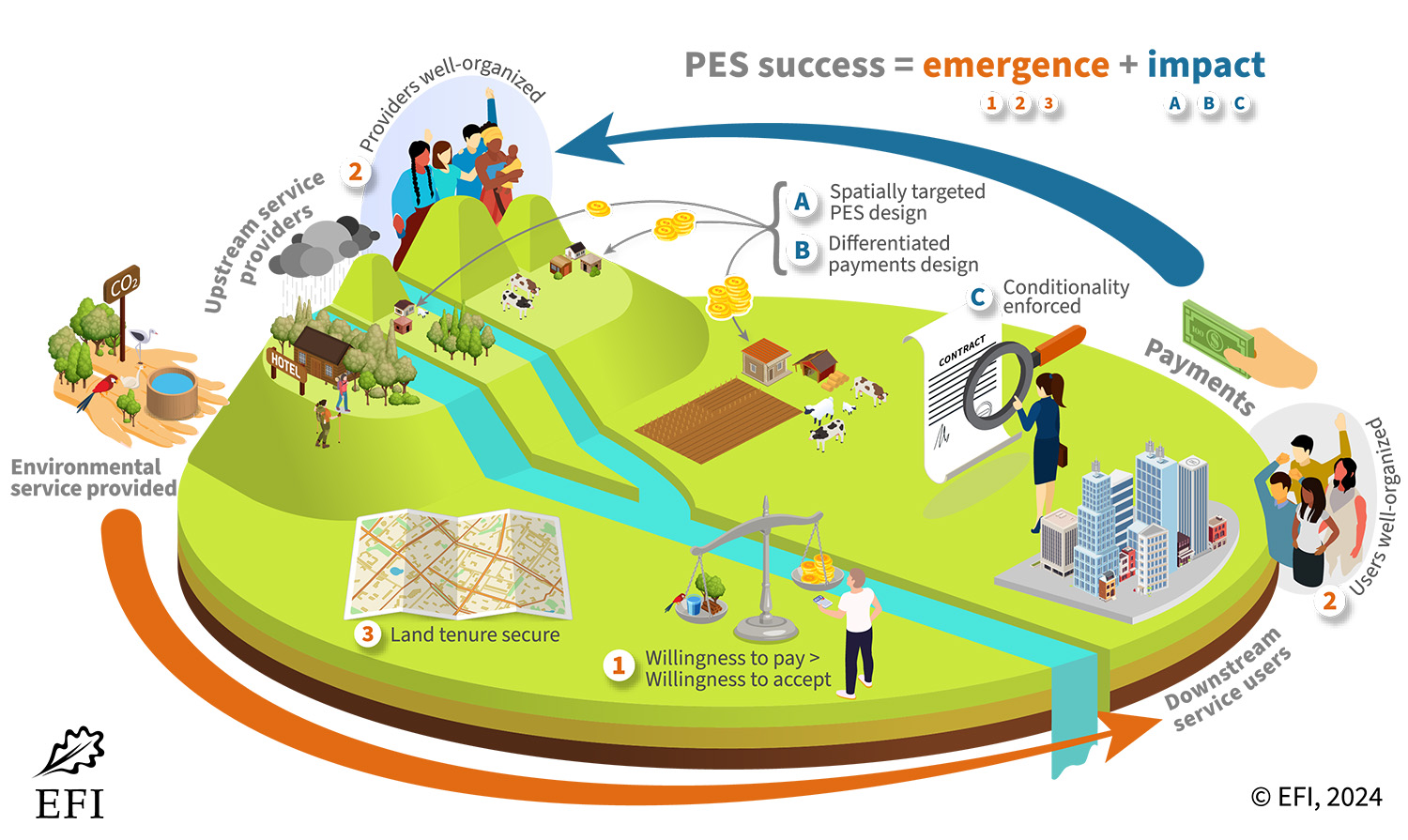

Given the double global crisis of climate change and biodiversity loss, stimulating forest owners to improve their forest management has become ever more important. Economic incentives such as payments for environmental (or “ecosystem”) services (PES) could help to better align supply and demand for forest environmental services, such as watershed protection or carbon storage. They are defined as voluntary transactions between service providers (i.e. forest owners and managers) and users, and are conditional on contractually stated rules of natural resource management. Most PES are about such contracts, rather than proper ‘markets’ with multiple stakeholders in demand and supply action. Recently the European Commission has published guidance for PES schemes.

- Private schemes: entail direct user payments from private service beneficiaries, e.g. from drinking water users or hydroelectrical companies, and thus constitute also an environmental finance tool.

- Public schemes: public-sector entities act on behalf of private beneficiaries in channelling conditional

subsidies to resource managers.

PES schemes have been around for a few decades, but have expanded much during this millennium. In Europe, agri-environmental schemes (e.g. for increasing on-farm biodiversity) have been the primary channel. Yet, some private and public forest PES and PES-like initiatives exist, e.g. through carbon offsets or the EU’s Rural Development Programme support to forest owners. Globally, PES have been used primarily to incentivize forest conservation, paying forest owners to deforest less.

What does it take to put a functional PES scheme into place?

I. For PES to emerge, certain preconditions are required:

- Applying basic economics: the willingness of service users to pay has to exceed the willingness of service providers to accept: otherwise, if the demand-side payments offered are insufficient to cover supply-side incremental forest management costs, voluntary deals will not fly. In Europe, much environmental management traditionally is in the public domain, which probably is limiting private willingness to pay.

- Service buyer and seller institutions work well: collectively coordinating action may be required on both sides. Lacking pre-existing institutions, people need to self-organize, including to avoid free-riding scenarios (e.g. service beneficiaries denying payment). In Europe, institutions customized to environmental services are less common.

- Need for safe land-tenure and access rights: only with these at hand can forest and other natural resource managers become effective service providers. Otherwise, third parties could jeopardize management. In Europe, typically land and access rights are defined better. In the tropics, this assumption often

does not hold.

II. Once working, how can we design and implement PES to achieve the best impacts?

- Spatial targeting of forest owners as service providers over others becomes essential, when limited service-user (or public) budgets make it impossible to enrol everybody. High service intensity, high threats/leverage and low costs constitute key targeting criteria.

- Differentiating payments, rather than paying the same per hectare, household or village, can greatly raise cost efficiency when the costs of provision vary a lot across landowners and managers, thus stretching budgets to achieve higher environmental returns. In Europe, differentiated payments have been more common than spatial targeting.

- Paying for environmental results (e.g. increased biodiversity), rather than actions (e.g. changed forest management) can sometimes raise effectiveness –

action-result hybrids are frequently recommendable. Agri-environmental PES have piloted result-based/hybrid schemes in Europe. - Without sanctioning provider non-compliance, PES becomes a “free lunch” – yet often PES rules are in practice ill-enforced and moral hazards abound. Very

little is known about non-compliance in European PES schemes.

Reference

Wunder, S. How can we make Payments for Environmental Services work? Policy Brief 8. European Forest Institute. https://doi.org/10.36333/pb8