Losing sight of the wood for the trees? – EU decision-making explained

Author: Doris Wydra, Salzburg Centre of European Union Studies (SCEUS)

Decision-making in the European Union often seems unduly complicated. National interests, local demands, European institutions, various stakeholders, and expert committees have a say when rules are made for the EU’s multilevel polity. And when it comes to the multifunctional role of forests, decision-making procedures may also vary depending on which issue relating to forests is at stake.

The choice of procedure depends on the treaty basis for the legislative proposal. This may not always be straightforward: in 1999 the European Parliament (EP) brought a case against the European Commission (EC) before the Court of Justice (CJEU), with a complaint that regulations concerning the protection of the Community’s forests against atmospheric pollution and against fire have been amended by using an inappropriate treaty basis – and thus the wrong procedure, which led to the exclusion of the EP from the drafting of the regulation. The consequence was the annulment of the respective legislative acts.i As the ‘right of legislative initiative’ rests with the European Commission, it is also the task of the Commission to find the right treaty basis for each legislative proposal.

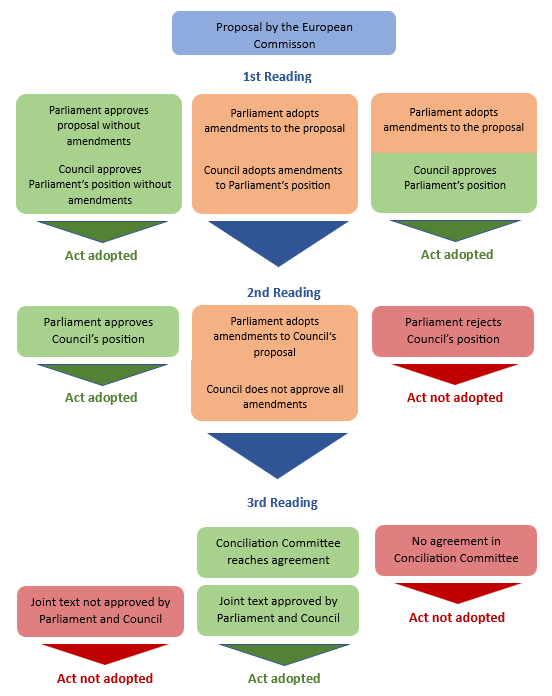

With the Treaty of Lisbon (2009) the “Ordinary Legislative Procedure” became the most common form of decision making in the EU. It now applies to most policy areas relevant for forests, among them agricultural policy, environment, climate action, energy policy and rural development. At first glance, it seems a complicated and long process of up to three readings: the Commission’s proposal goes through a first reading in the EP and the Council of the European Union, with the EP adopting, amending or rejecting the draft. If the EP adopts or amends the draft, the Council either (a) approves the Parliament’s position, in which case the draft is adopted or (b) amends it and thus moves the process to the second reading. If no agreement between Parliament and Council is found at this stage, a Conciliation Committee is convened, bringing together representatives of the 27 member states in the council and 27 Members of Parliament. Its task is to come up with a joint text within six weeks, which is again put to a vote in the EP and in the Council. In practice, hardly any proposal makes it to the conciliation stage. Thanks to the trilogues – informal inter-institutional negotiations coming up with provisional agreements that are acceptable to both the Parliament and the Council – more than 80% of the legislative procedures end with the first reading.

Ordinary Legislative Procedure (adapted from European Parliament: Handbook of the Ordinary Legislative Procedure, 2020).

But a lot happens in the background of the ordinary legislative procedure, which is probably best illustrated by the example of the recently adopted regulation of deforestation-free products. In 2019, the Commission presented proposals for a better protection of forests around the globe in a communicationii. In 2020 the European Parliament conducted an added value-assessment and issued its own legislative-initiative report, calling on the Commission to present a legislative proposal. The Commission followed up with a public consultation on the suitability of different demand-side measures to address deforestation and forest degradation because of EU-consumption, and finally presented a proposal for a regulation on 17 November 2021 to hear stakeholders’ voices. The ENVI Committee of the European Parliament adopted its report on this proposal in July 2022; the Council had adopted its general approach already in June 2022. Trilogue meetings took place in September, November and the beginning of December 2022,iii successfully ending with political agreement. The formal adoption in both institutions ends the procedure in first reading.

EU legal acts usually are textbook examples of European political bargaining. The European Parliament, representing different party – and thus ideological – positions, and the Council of the European Union, where ministers defend member state interests have to find an agreement on sometimes highly disputed issues for a new piece of EU legislation. But sometimes, the issue at hand demands less political bargaining, but rather more technical know-how. In this case, EU law allows the European Commission to adopt “delegated acts” after consulting expert groups, composed of representatives from each EU country. One practical example of this is the “Commission Delegated Regulation” determining forest reference levels to be applied by the Member Statesiv for the period 2021-25 in tonnes of CO2. The Commission acts here on a delegation granted by a legal act (in this case the regulation on the inclusion of greenhouse gas emissions and removals from land use, land use change and forestry in the 2030 climate and energy framework) and is strictly confined by this delegating act in its action. Parliament and Council still may revoke the delegation or object to the resulting delegated act.

Contrary to the Ordinary Legislative Procedure, special legislative procedures generally put the Council in the lead and provide the EP only with the right to be consulted (consultation procedure) or the right to (withhold) consent (consent procedure) but not the right to amend.

The consent procedure is particularly relevant for the conclusion of international agreements of the EU, e.g. the 2006 International Tropical Timber Agreement, to which the EU became party by a Council Decision,v after consent was given by the EP.

The consultation procedure is reserved for sensitive areas with financial implications. While the EP may approve, amend or reject the Commission proposal, the final decision is with the Council – and thus the member states – as it is not legally required to take Parliament’s position into account. The current Commission proposal for a revised Energy Taxation Directivevi with the aim of aligning the taxation of energy products with the EU 2030 energy targets and subjecting fuel wood, wood in chips, wood waste and wood charcoal to taxation will follow this line of procedure. As it concerns tax matters, unanimity is required in the Council. Already in April 2019, the Commission published a Communicationvii, where it stressed that the requirement of unanimity does not live up to the ambitious goals the EU has set in field of energy and climate policy. It urged the use of the so-called “passerelle clause” in the Treaty, giving the Council the competence to decide unanimously that environmental measures of a fiscal nature could be adopted under an ordinary legislative procedure. This has not happened yet.

References

[i] ECJ 25.02.1997, Joined cases C-164/97 and 165/97, European Parliament v Council of the European Union, ECLI:EU:C:1999:99.

[ii] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Stepping up EU Action to Protect and Restore the World’s Forests, COM/2019/352 final, 23.7.2019.

[iii] See legislative train schedule/ European Parliament available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-a-european-green-deal/file-deforestation-and-forest-degradation-linked-to-products-placed-on-the-eu-market

[iv] Commission delegated regulation (EU) 2021/268 of 28 October 2020 amending Annex IV to Regulation (EU) 2018/841 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the forest reference levels to be applied by the Member States for the period 2021-2025.

[v] Council Decision of 78 November 2011 on the conclusion, on behalf of the European Union, of the 2006 International Tropical Timber Agreement (2011/731/EU)

[vi] Proposal for a Council Directive restructuring the Union framework for the taxation of energy products and electricity (recast), 2021/0213 (CNS), 14.7.2021

[vii] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council. A more efficient and democratic decision making in EU energy and climate policy, COM(2019) 177 final, 9.4.2019.