On the verge of a nervous breakdown

Do you know that kid whose parents want it to excel at music and to take piano classes at the age of six? Only to then also get enrolled at the local football club, arts class, scouting, ballet, mathematics tutoring class, swimming and theater lessons? Well, that kid is the forest.

This story starts with some letters that were addressed to the forest and that people mistakenly sent to the European Forest Institute. To do them, and the forest, justice, we decided to publish some extracts here.

“Hello forest, we need to produce renewable energy. Is it ok if we shorten the rotation and harvest more biomass?”

“Hey forest, don’t you know that climate is changing? We need you to increase in volume in order to store more carbon.”

“Hi forest, we just discovered that you actually also store carbon after your death in the form of furniture and wooden buildings. Is it ok if we cut a bit more?”

“Dear forest, you mean a lot to us just as you are so please don’t ever change. Just stay exactly how you are now!”

“Forest, you are not cooperating to achieve our habitat directive goals, so we are forced to change your species composition and maybe transform parts of you to heathland if you don’t mind.”

“Hello forest, we would like to take you out of use and restrict any human access to you. Trust us, you will be happier alone. It’s not you, it’s us. You will get over it.”

“Hi forest, is it ok if we build some hiking trails in you? And a mountainbike trail. And maybe one for horse riding. And maybe also a picnic site and a shelter for if it rains. And a parking space. That will be all. Thanks!”

Signed: Society

Forest therapy

If forests were more like people, they would probably get a collective burn-out because of all the expectations that rest on them. How could one not succumb to all this pressure and these contradicting demands?

Conflicts on forest-related issues are often expressed using the same two categories: forestry and nature conservation. Members of these two groups are often perceived as the two main antagonistic factions that set the tone of the debate. However, this is not necessarily the case (anymore).

The increased focus on climate change mitigation and the lack of clarity on how exactly forests can help with it, is a new player in the field. Forests are no longer seen as either a source of raw materials or biodiversity, but as a potential carbon sink.

Secondly, our rapidly urbanising society has in a few decades drastically altered its relationship with nature. And this relationship is largely visual. We live in a world full of visual stimuli which only leave us alone when we sleep – if at all. Communication that used to be transferred through the radio or newspaper is now available in fancy illustrated magazines, blogs or videos. The amount of information we get bombarded with is too much to handle, so we often resort to what comes most natural to us: emotions. This also holds true for forest-related topics. Images of burning woodlands, homeless orang-utans and monstrous harvesting machines dominate most people’s idea of the state of the world’s forest (even though the situation is not all that bleak).*

This negative image that reaches us through social and other media might explain why also in Europe, where many positive forest trends can be observed, people tend to be extremely critical of forest management.

Looks matter

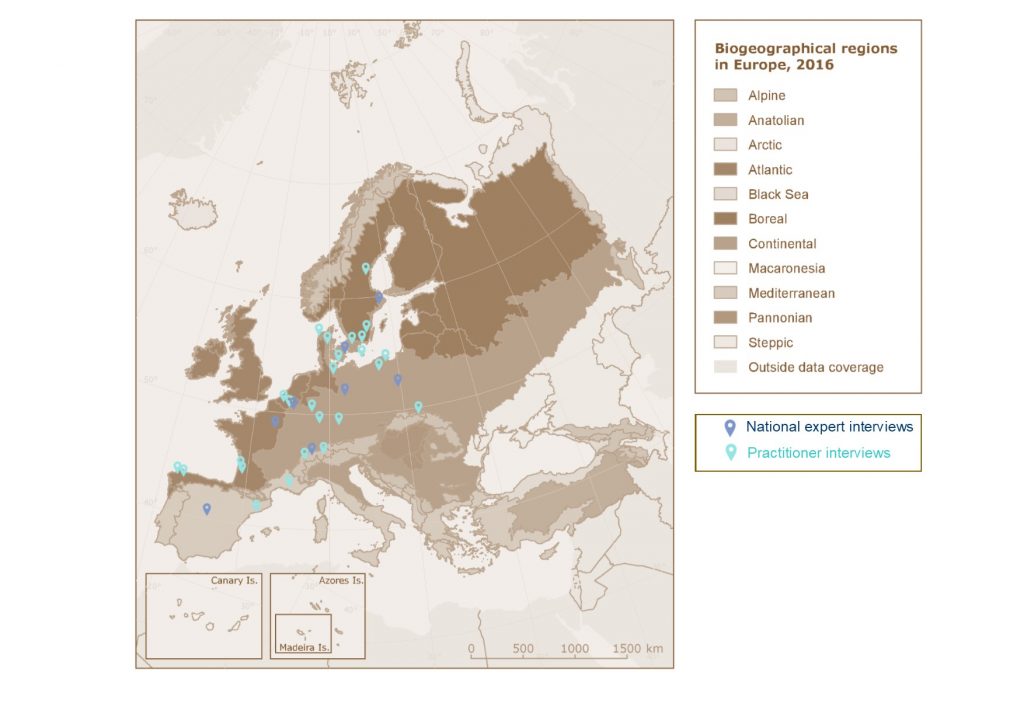

For the European Forest Institute’s INFORMAR project, we conducted dozens of in-depth interviews in nine European countries, on the facilitating and impeding factors that drive integrated forest management.

One of the clearest findings was that conflicting societal demands can make it hard for European foresters to do their job, especially in urban environments. While on the one hand the interviewees admit that the environmental awareness has increased, on the other hand they feel that people’s understanding of land use has decreased. There is a sense that many environmental concerns are actually more aesthetically motivated than anything else. People do not like the landscape around them to change. People like big trees. As a consequence, people do not like (big) trees to disappear. It is however impossible to comply with the increased demand for local and renewable raw materials without attributing a utilitarian use to the land. You cannot live in a wooden house full of IKEA furniture without cutting trees. The alternatives – concrete, steel, imported wood – are hardly more appealing to the environmentally aware. If humans are not willing to rethink their consumption habits, we can only try to consume as sustainable as possible.

Many people like the idea of locally produced food, but for wood the situation is slightly different. This is probably because annual agricultural crops do not have the same long-lasting impact on the landscape as forests. Since forests are usually very long-living entities, people tend to see them as eternal and unchangeable. Many of the interviewees in our studies arrived to similar conclusions. However, instead of seeing the aesthetic desire of society as a problem, some foresters use it as an opportunity to increase societal acceptance of forest management. The perception of what is visually appreciated is rather unison. People (including forest managers) seem to like forest stands with different tree species and a diverse structure with young and old trees intermixed. Big and monumental trees are a plus.

Luckily, there are forest management strategies that can provide all of these perks in a managed stand. Continuous cover forestry where different forest functions are integrated can be an option for forest managers in certain conditions. Preserving big old trees, especially next to trails, is not only beneficial for biodiversity and regeneration but also looks nice. Forest edges composed of various shrubs don not only provide food and a habitat for many species, they are pretty. Species diversity does not just limit risks related to pests and diseases, but makes the forest more beautiful.

If forest managers want to tackle the social issues that their profession faces in these changing times, they need to evolve with time. An important strategy is to use communication tools that have proven to be effective in other domains, and to be pro-active and dynamic. It is crucial to show people the bright sides of forestry and to reverse the downward spiral of negative perceptions.

PS: While forests are definitely confronted with severe threats and problems, there are also positive evolutions that are all too often downplayed. For instance, global forest surface is increasing, burned forest area has been decreasing for years, the earth is getting greener and sustainable forest management is becoming more and more self-evident. Let’s work together to extend this list.